The Wanderer

The Creature awakens into a world of blinding whiteness—fitting, since he’s known nothing prior to waking up, and has never opened his eyes. In this moment as the game begins, we are equally as disoriented as he is; we are in control of his body, but can’t see where we’re going, as the screen is obscured by a thick white fog that he can only dispel by blundering blindly through it. His narration appears at the bottom of the screen in eloquent writing (we later learn that he is telling us this story in retrospect, guiding us through the harrowing first months of his life) but what we actually see is cluelessness. Having been through literally any high school or college literature class, we know what he doesn’t—that he is an experiment, an amalgamation of corpses come to life and promptly abandoned. But the Creature, having no concept of life, let alone science, doesn’t know this. He’s just left alone to stumble through the foggy, incomprehensible lab of Victor Frankenstein and find his way out.

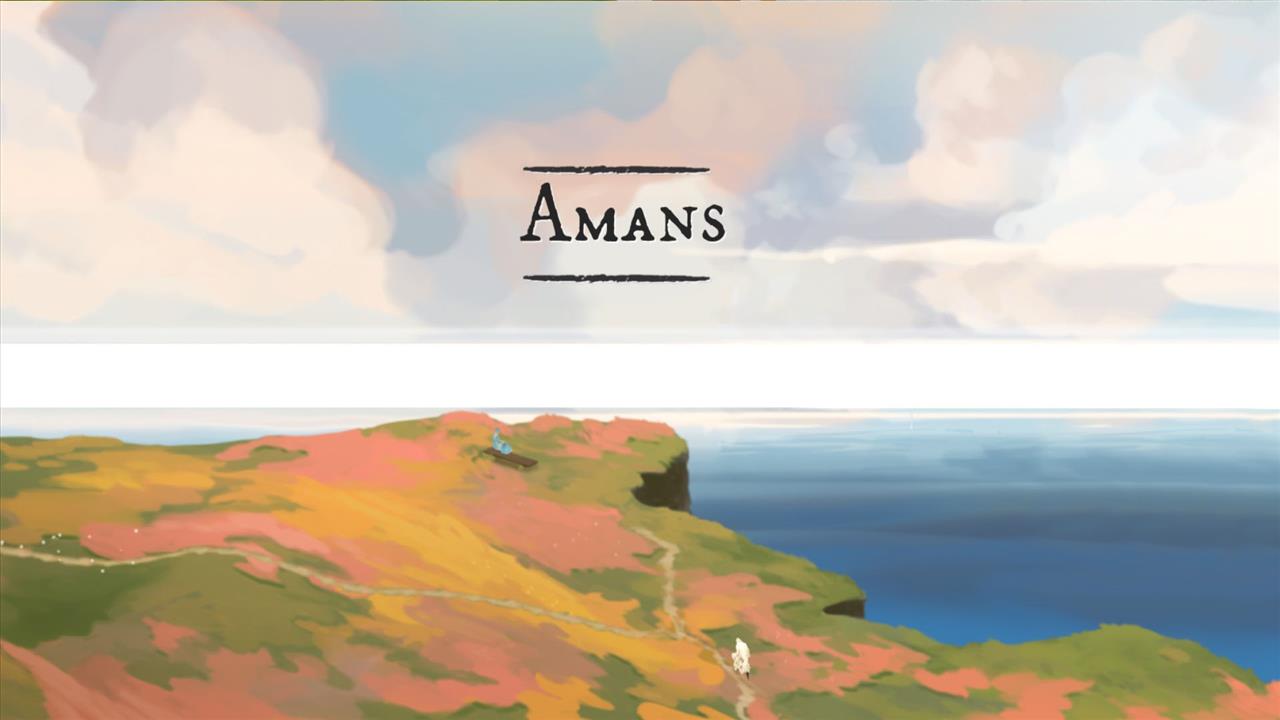

And then outside? Color. Where the inside of Victor Frankenstein’s house was a grim monochrome, the Creature stumbles into a paradise outside, and in this contrast sets the stage for a powerful, beautiful game.

Right from the outset, The Wanderer enraptured me with its clever use of color and sound. Where we as players would immediately recognize the setting of a laboratory and a house, the Creature would not; to create a sense of unfamiliarity and disorientation in the player, they obscure the screen in a thick white fog, and then reveal the world in indistinct shades of gray. When he reaches the outdoors, small patches of watercolor emerge, in stark contrast to the grim grayness of the lab; the more he explores, the brighter everything becomes, and the more color he sees. When he walks, music plucks to life; when he stops, the music stops as well. It creates an air of whimsy, almost, like a child is taking their first foray into a flower garden. Soon, he is overwhelmed by the new sights and loses consciousness; he wakes up in what can only be described as paradise, with a bubbling stream and a young deer and bright berries.

This clever use of lighting and color continues throughout the game, and interplays with another key element of the storytelling. For the entire beginning of the game, the word “monster” never crosses the Creature’s mind. He doesn’t yet know that he is what people would call a monster; he has no concept of himself at all. As such, we as players are responsible for shaping his first experiences of the world, and how he perceives them. In paradise, drinking fresh water or eating juicy berries will cause the screen to surge with color, beautiful music swelling to match. However, if we choose to provoke a snake or taste carrion (because hey, not even paradise is perfect), the screen will go dark, brambles will curl out from the corners, and the music will turn dissonant. Again, like a child—because technically, the Creature was just born—his perception of the world is shaped largely by his initial experiences, with no goodness or evilness inherent to his being.

The themes that The Wanderer explores throughout this learned-behavior style of gameplay—innocence, beauty, loneliness, fear, otherness—make the former literature student in me giddy. The Creature very much reflects his environment; for example, when he eventually encounters children, they readily welcome him into their game of kickball, but when the parents encounter him he is chased away with torches. This very much reinforces the idea that behaviors and prejudices are learned and not natural, and the game is exceedingly good at keeping that common thread throughout the course of the game. It has to be; it is a novel-turned-game, after all, so if there wasn’t any sort of analysis to be had here it wouldn’t be a very good game at all.

After his whirlwind start to life, the Creature finds himself hiding in the shed of a lonely cottage, and it is here that the sheer creativity behind this game shines once again. The creature can’t understand the humans as they talk; their dialogue is shown as speech bubbles above their head, but with gibberish runes instead of words. We—the Creature—can’t tell what they’re saying as we eavesdrop. However, after he, ahem, borrows the encyclopedia of the cottage’s inhabitants, reading for season upon season, the runes gradually start to change. He can recognize a word here and there, just enough to tell the problems of the three inhabitants, and he can choose to help remedy their problems. For example, in fall they worry about trapping a rabbit—which is about all the Creature can decipher—and the Creature can act as their mysterious guardian angel if we so choose to. Trapping the rabbit results in a positive experience for the human; doing nothing results in a negative experience. Thus the trend of learned behavior—and consequences, which I absolutely love in games when they’re done right—continues.

The parallels and symbolism in The Wanderer are off the charts significant. If the Creature chops wood for the family in the cottage, they praise God for saving them and keeping them warm—but what is God? Is God the Creature of corpses hiding in their shed, choosing to perform or abstain from good deeds depending on his perception of reality and how he is received? Was the Creature’s journey between paradise and human civilization similar to the fall of Man? When he seeks to build a sculpture—dropping the raw line “Were it to be repulsive, I would love it like myself,” by the way—does it parallel his own birth as an amalgamate of abandoned, decrepit, cold pieces? It gets intense; though these parallels are never explicitly mentioned, they couldn’t be more obvious, and yet are presented to the player with such grace that I don’t at all feel like there’s an English teacher lecturing me. I feel like this game is revelatory. Like it’s teaching me something. Like I’m watching the formation of a life, and through that lens examining my own.

This is not a horror game. Though Frankenstein’s monster has become a pop culture icon, surging in popularity around Halloween, The Wanderer hearkens back to the true nature of the Creature—the complete and utter loneliness of being a monster, and not seeing yourself as a monster until other people label you one at that. Mary Shelley’s Creature has a hard life. The Wanderer’s Creature is no different. In an homage to Shelley’s book, The Wanderer puts a gorgeous twist on the well-known tale, and lets us live in the shoes of an outsider while reexamining our own perceptions of the world, as well as why we perceive it the way that we do.

If you’re a fan of literature, games with meaning, or unique art styles, then you won’t regret playing The Wanderer: Frankenstein’s Creature. A calm, sorrowful, and beautiful adventure awaits you, with poignant storytelling from the very Creature you control. The landscape will splay out around you in vibrant watercolors, and the music will guide your emotions. There is no thrill, no fast-paced adventure, no strategy, so if that’s your cup of tea you may want to look elsewhere. Otherwise, this game is a beautiful book come to life, and is absolutely worth the play.

Rating: 9 Class Leading

* The product in this article was sent to us by the developer/company.

About Author

I've been involved with games since I was a little kid, when I would watch my father play World of Warcraft for hours—and later, of course, mooch off of his account. I have a cobblestone background of creative writing, newspaper journalism, and multi-platform gaming, and I intend to add more stones to that mix as I get them. Excluding sports, I'm a fairly versatile player and will play whatever I can find, though I have a soft spot for lore-intensive games and fantasy. Personal interests include the interplay between history and video games, especially with games that contain archaeological elements—however fantastical—such as Horizon Zero Dawn and the Tomb Raider franchise.

View Profile