Small Radios Big Televisions

The 1980s is the new nostalgia—in case you hadn’t noticed. That nostalgia comes across in the warped video tracking on a 15-pound VCR. In the long, black ribbons spooled inside of a cassette tape. In the polygonal, retro-futuristic visions of the pre-internet world. Small Radios Big Televisions eats up the analog technology of the Reagan Era, repackages it with an indie ambient noise soundtrack, and swoops you around the LOST what’s-down-the-hatch architecture and aesthetic.

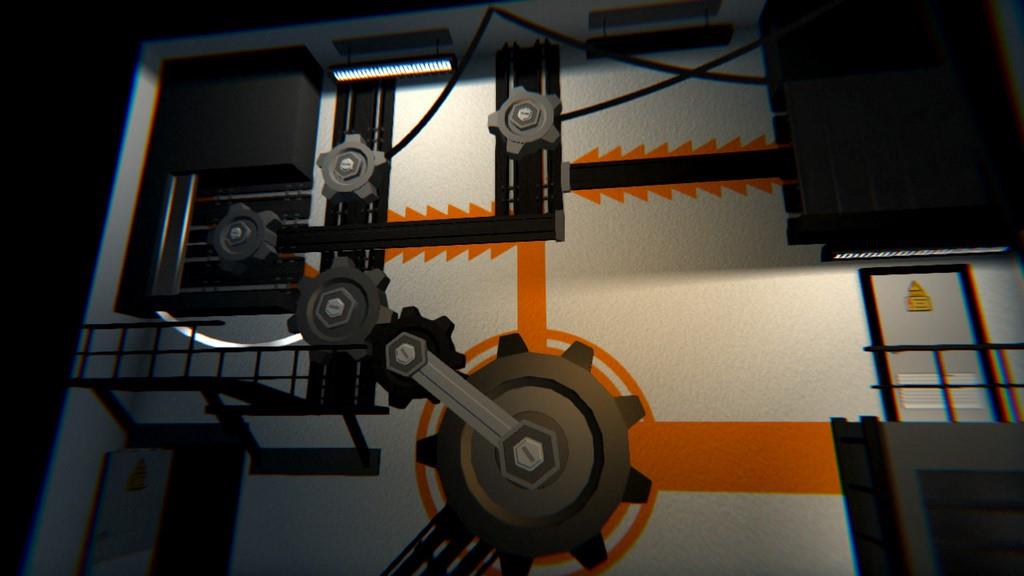

Small Radios Big Televisions is a puzzle game. On the surface, it feeds you recognizable elements. In other words, you flip switches, affix gears, and push buttons. You light paths, drain water, and power up generators. You spin dials, align symbols, and read the writing on the wall. Plus you find cassettes. They’re the kinds of cassettes you play in a Sony Walkman. Well, except you play them in something bulkier, chunkier; something more like a Commodore 64 Datasette tape player. But these cassettes don’t play all the greatest hits from the ‘70s and ‘80s. These cassettes bridge the 2.5-dimensional levels with the 3D polygonal levels.

Conventional puzzles populate the 2.5-D side-view levels. They look kind of like Fez structures from the outside, Portal interiors from the inside. The 2.5-D levels are where you have your knob-turning, switch-flipping puzzles.

But the narrative puzzle, the what’s-really-going-on-here? puzzle, plays out in the 3D worlds of the cassette tapes. Finding these cassette tapes floating around the levels, then popping them into your “TD-525” cassette player, opens up a virtual world of often-surreal, sometimes-abstract imagery. While these cassette worlds are three-dimensional, they’re on rails. They let you look up and down, left and right, but you won’t be walking around on your own. You’ll row, row, row your boat gently down a stream of consciousness, looking around the 360-degree panoramas swimming by. After playing Small Radios Big Televisions, I’m not entirely certain that developer Fireface hasn’t drilled a few hours’ worth of subliminal messages into my puzzle-addled gamer brain.

I’m trying to use the term “virtual world” lightly, however, since we’re now living in the future, and virtual reality is only a PC or PlayStation away. But within the context of the game, it’s worth meditating on these virtual worlds for a few minutes. Part of the game is happening when you’re simply taking in the sights and sounds around you. Sure, you can play the tape, snatch the green dodecahedron of a door key, then bounce out as soon as possible. But there are neutral moments to fixate on for a little bit, if you’re willing. Stare into the dot-to-dot complexity of a molecular compound that seemingly houses computer components. Ride a train track in an endless circle around a cliff’s edge. Stare into the rainbow-framed face of a polygon man on a couch with a tape deck and a VR headset on the table next to him.

So, yes, you might get nothing out of your time spent in those virtual worlds. Whose fault is that? On the other side of that coin, perhaps that’s the point. Maybe getting nothing out of these surreal sessions ends up telling you all you need to know about yourself, in that space. But I recommend spending more time with those visions. Spend more time circling that train track, watching snowflakes dance over the rails, as the cliff on one side of you represents the safety and comforts you know, all while wanting to fall headlong into the other side, open to the distant clouds and hills.

No single puzzle is overly complicated. That doesn’t mean I didn’t sit there scratching my head, though. I had a few of those. It wouldn’t be a puzzle game if you didn’t have to stand up and take a breather once in awhile. Only a couple times did it feel like I’d approached the puzzles in the wrong order. Most of the time, the gradual incline in complexity was reasonable and welcome.

Each level seems thematically centered on the idea of harnessing power: coal and human labor, air conditioning and gears, plant nature and the inner mind, gas-fired furnaces and hydraulic systems. That harnessed power then goes into the digital and beyond. It goes into the realm of thought, the realm of virtual worlds, and into (some kind of) transcendence, (some kind of) experience beyond the normal physical level.

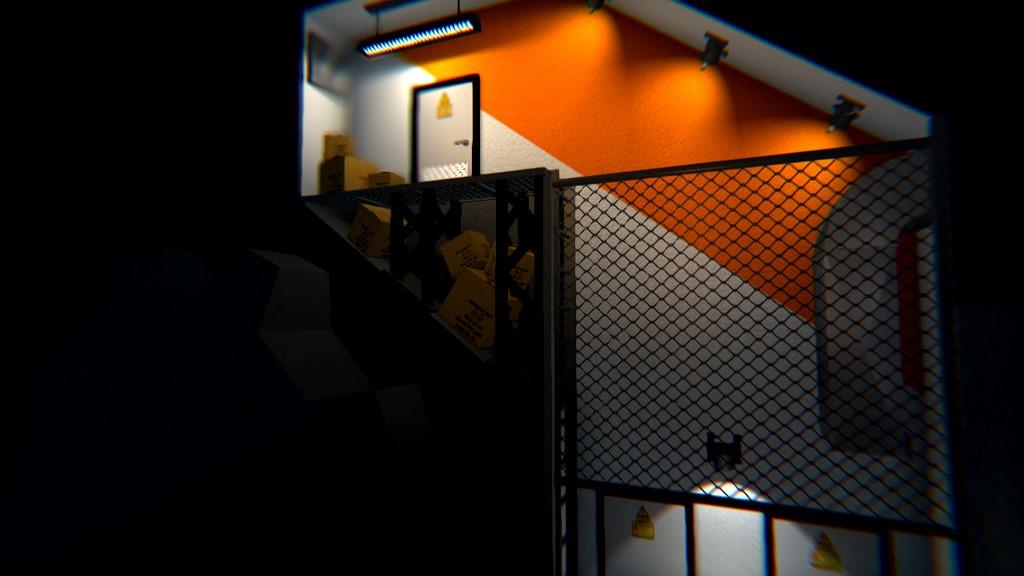

That’s the answer to Small Radios Big Televisions. The answer is at the top. The answer is in the mind. As far as the architects of these in-game structures are concerned, the answer is to build a tower that reaches all the way up to mankind’s consciousness, like a psychological Tower of Babel. That, according to the game, is the highest level of existence: not to go up, but in. And all of these manufacturing processes seemingly lead up to the assembly of these cassettes, in order to spread this new religion to consumers around the globe. Cardboard boxes are stacked about, on standby, ready to fill purchase orders full of this new science, this new world of the mind, that can be preached to any and all. Just a nominal fee, plus shipping and handling, is all it will cost you, it seems to say.

In the end, even the manufacturing processes are as automated as much as possible. It eventually evolves from images of fists holding wrenches to vacuum tubes shuttling product around. The puzzles—the literal and metaphorical obstacles in life—have been removed. The human labor has been removed. The only human resource with any remaining value is the human mind. Stairs are largely replaced with ramps. Ladders are mostly replaced with elevators. All the hard work is done.

Yet the story of these human minds resisting transformation, or simply trying to put this transformation into perspective with words and pictures, still make their way around with buckets of paint and paint brushes to tell the story. They put the writing on the wall. They convey the resistance, and then acceptance, of the human mind to turn itself from a creature that was one with nature into a creature that is one with itself.

After reaching the end, it’s hard to know if the story has a happy ending or not. You’ll decide that for yourself.

Fireface walks a fine line between hints and handholding. The writing on the walls seems hamfisted at times, poignant at others, but hey: When I’m finally sitting in a retirement home, gumming a bowl of mac and cheese, asking the caretakers for one more bowl of spumoni ice cream—and it’s obvious I’m completely off my rocker at this point—the first thing I’m going to do is get a bucket of paint so I can draw obscure, puzzle-rich elements on the walls of my retirement community. That’s when I’ll know I have arrived. That’s when all the work of my life is done. That’s when the only thing I’ll have left to do is ascend an elevator into my own mind.

Everybody’s gone to some kind of rapture in Small Radios Big Televisions. It’s a rapture devoid of physical labor or mental exertion, but one of technological transcendence. It’s a game of sensible puzzles, though a few still stumped me. It’s a game owning its simple art style, but assembles itself in broad strokes with bold geometry. And it’s a game of meditative musicality, though willing to occasionally strip down my senses or hit rewind on my complacent ears. Small Radios Big Televisions is short, but it takes you deeper, once you stop working so hard for it.

Rating: 8 Good

* The product in this article was sent to us by the developer/company.

About Author

Randy gravitates toward anything open world, open ended, and open to interpretation. He prefers strategy over shooting, introspection over action, and stealth and survival over looting and grinding. He's been a gamer since 1982 and writing critically about video games for over 20 years. A few of his favorites are Skyrim, Elite Dangerous, and Red Dead Redemption. He's more recently become our Dungeons & Dragons correspondent. He lives with his wife and daughter in Oregon.

View Profile