Fracture (Hands On)

Written by Randy Kalista on 9/28/2008 for

PS3

360

More On:

Fracture

The Presidio of San Francisco served as a military post under three separate nations: Spain from 1776-1822; Mexico from 1822-48; and the United States from 1848-1994. But now, as I walk with a group of videogame journalists hailing from sites like GameDaily, Kombo, and Gamer2.0, an expectant hush falls over the group. Not from any gravitas of history that reaches back to the birth of the U.S., but because the Presidio, for nearly a decade now, serves as the locus for many things George Lucas.

We’re treading hallowed ground and we know it. With an awe typically reserved for Gothic cathedrals and Wonders of the World, we tip our chins up and gape around at the stylistically-preserved historical architecture. We also wonder if at any moment George Lucas himself might emerge from around a bend in the pathway, or stroll out of any one of the buildings, coffee in one hand, lightsaber in the other.

We don’t see George Lucas or lightsaber at his hip, but this is indeed the home of Lucasfilm, LucasArts and ILM (Industrial Light & Magic). These arms of George’s empire are encased in a building known as the Letterman Digital Arts Center -- built from the ground up to preserve the architectural style of the original hospital that was on this particular site, but containing all the amenities of a contemporary office space. And if it wasn’t for the Yoda fountain in the courtyard, you might not fully realize at first that you’re standing at the center of the Star Wars universe.

Chris Cook, Public Relations Specialist for LucasArts, is walking and talking our way through the hallways toward our destination: The LucasArts Gameplay Room. Two trashcans (already stuffed with lidded coffee cups and snack wrappers) sit outside the Gameplay Room’s door, reminding us that food and drink are a no-no inside. And as we step through the door we’re greeted by two rows of tables, each table lined with ten gaming stations heavily-equipped with a PC, Xbox 360, PS3, PSP, and HD monitor. Each monitor has a handwritten nametag propped at the top with designations like “Xbox 360 Italy” and “PS3 Japan,” presumably to help us remember which station we were at in the event of a restroom break. Cool air blankets the room through copious vents positioned on the ceiling and floor. The chairs are ergonomic perfection. And the main menu for Fracture, developer Day 1 Studios’ latest high-budget baby, is humming on the screens (“These aren’t the best monitors,” says a Day 1 dev as I manually brighten the dark screen through Fracture’s options menu).

To get you up to speed: Fracture takes place in the year 2161. Day 1, developers of the award-winning MechAssault series, wanted to look at hot-button topics of today like stem cell research, the Human Genome Project, and global warming, then fast-forwarding their potential effects 153 years -- focusing on a few worst case scenarios, but trying not to grow preachy in the telling (“We don’t want to slap players around with a case in Ecological Policy”). Nonetheless, global warming has raised water levels, turning the Midwest into a great inland sea. The East Coast, now dubbed the Atlantic Alliance, protected itself from a similar fate by utilizing Terrain Deformation technology: the ability to raise and lower the landscape at will. The West Coast, now the Republic of Pacifica, followed suit. Not only geographically, but ideologically the United States became a house divided. The Atlantic Alliance advanced itself technologically by utilizing cybernetic enhancements. The Pacificans resorted to DNA splicing and genetic manipulation. Washington D.C. grew increasingly displeased with the West and, far too late in the ballgame, decided to criminalize the Pacificans’ research and actions.

An Atlantic Alliance team, spearheaded by Colonel Roy Lawrence and his adopted son Jet Brody, is sent to a dried-up San Francisco Bay (“We wanted to incorporate water physics with Terrain Deformation, but that’s one place where the programmers successfully punched us in the face and we fell on the ground,” said Day 1) in order to bring the leader of the Pacifican resistance, Colonel Nathan Sheridan, back to D.C. to be tried for war crimes and, assuredly, treason.

Consider yourself briefed.First up on the LucasArts Gameplay Room agenda is an hour’s worth of Fracture’s single-player campaign. It begins with the in-game tutorial, which is 100 percent identical to the demo released on Xbox LIVE and PlayStation Network September 18th. The showdown between Jet Brody and Colonel Sheridan comes to a head at Alcatraz Island. Sheridan, naturally, isn’t ready to walk away in cuffs, and the chase is on. Previously unknown through Jet Brody’s intel, however, is the fact that Sheridan has been preparing an all-out war effort for longer than initially conceived. Things will indeed get worse before they get better.

I push full-bore through the Alcatraz Island demo material until Jet Brody hops on a dropship and is airlifted towards his next target: the Golden Gate Bridge. Anti-aircraft gunfire cuts that objective short during a cutscene. Jet Brody’s ride is picked out of the air and goes down hard. He’s the sole survivor amidst the wreckage, but his comms are clean and his commanding officer, Colonel Lawrence, instructs him to press on -- army of one-style -- and proceed to the bridge as ordered. Jet Brody may have jokes, but he’s not insubordinate. Not yet, anyway. Both the Pacific and Atlantic forces seem suspect.

As I quickly acclimate to the tools of the trade -- to include the wrist-mounted Entrencher (“The key that unlocks the world of Fracture,” states Dan Hay, Executive Producer and Art Director for Day 1), Tectonic Grenades (which raise the terrain), and Subsonic Grenades (which do the opposite) -- I steer Jet through a complex of mammoth bunkers housing the two anti-aircraft guns that blew up Jet Brody’s ride.

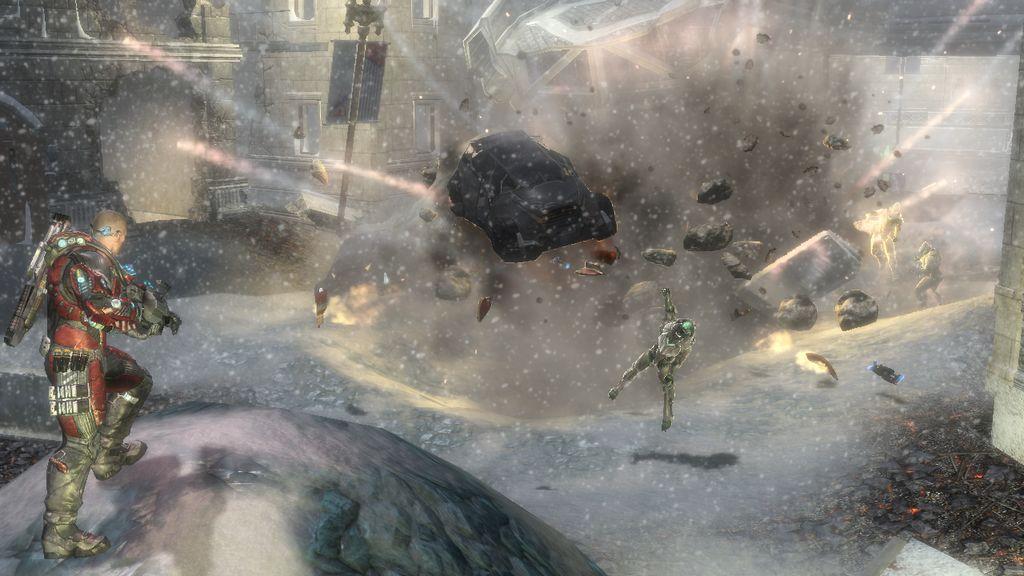

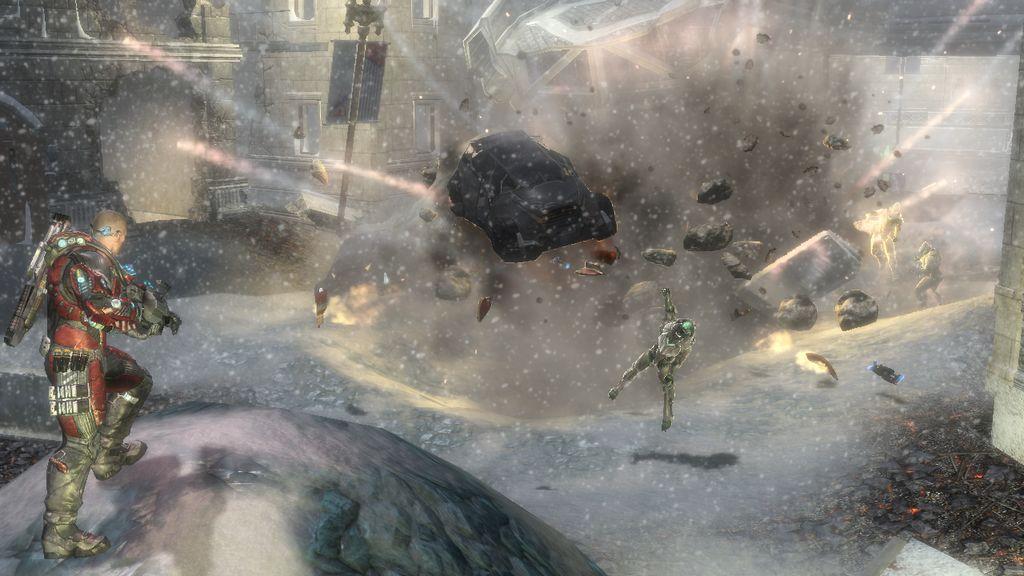

Along the way I face plenty of Pacifican fodder, tossing them into the air when I burst the ground up from under them and skeet shooting their ragdoll bodies on the way down. Other times I raise terrain to provide immediate cover in the often times wide-open battlefields, or dig a trench to grant myself breathing room from the flying bullets overhead. The enemy is more than capable of utilizing its own tools for terrain deformation, flanking the mounds of earth from the left and right, climbing right over the top to gain a height advantage over my position, or falling back in order to recover shields. Creating a seemingly strong enemy AI in a corridor shooter like F.E.A.R. is all well and good, but that game’s AI didn’t have even a fraction of the variables being tossed about in Fracture. Here, as the battlefield tosses up and down like a stereo equalizer, the AI has to be able to cope with keeping track of a player that moves not only on the X-axis, but on a constantly variable Y-axis as well -- and we’re of course not just talking about Y-axis movement on a couple stationary staircases. While the AI may lose track of you on the Casual difficulty level (you will hear the bad guys shouting out, “Where’d he go?”) the hardcore difficulty setting creates a drastically different scenario, with a relentless enemy that -- even if it doesn’t know your exact location on the other side of that mound -- is willing to toss a grenade up and over at your last estimated location. Like 3-D Battleship.

The Day 1 team tells me that Fracture was initially conceived to be a first-person shooter, but realized how disorienting it was to raise up large mounds of dirt in front of your face that took up your entire field of view. Day 1 quickly concluded the need to pull back to a third-person perspective, just to keep a player’s bearings in the radically chaotic fields of battle. The only drawbacks to that decision was the lack of a near-object fade that can sometimes have foliage (a rare occurrence) that’s hanging five feet behind you suddenly choke a player’s line of sight. Another issue is that Jet Brody’s firing stance often has him holding a rifle down by his waistline: He’s literally shooting from the hip. And reconciling the difference between that low-slung firing position and the eye-level reticule can be a chore for the player. Jet Brody can also kneel behind objects, but it’s only under infrequent circumstances that he can fire at enemies from that kneeling position. A player has to pop up, fire off some rounds, and then recover.Day 1 also, in the best interests of the wildly changing landscape, had to do away with allowing a prone position, which is always ideal for sniping, but awkward in implementation when you could be humped over a hill one moment and bent over backwards the next at the bottom of a trench. They also didn’t allow Jet Brody to ‘hug’ up against cover. Very little is stationary on a Fracture battlefield, with crates, barrels, and boulders getting tossed around with trampoline-like enthusiasm, not to discount the screen-shaking explosions, dust, and debris scattering every which way. And while there’s little “verticality” to worry about (an up and coming buzzword in action-shooter gameplay), having to draw a bead on an enemy that’s rarely on a level plane with you can be challenge enough.

Not only is Terrain Deformation required to manage the battlefield, it also serves as a puzzle-solving tool once the bullets stop flying. Jet Brody doesn’t make a habit of looking around enemy structures for door keys, though he can push gates open with the Entrencher. He may not have a person on the inside opening gates for him to progress through, but he might lower the terrain to uncover a hidden tunnel or weak point in the infrastructure. Or a set of stairs may be blasted completely away, but reaching the second story of a building is doable with Spike Grenades (which lifts a pillar of earth into the sky that can be ridden to upper levels). It is a world built around and for Terrain Deformation. Little of what I previewed is designed without this tool in mind, and without it there’s very little progression through the world.

I’ve been proceeding with a stop-and-go frequency through an underground Pacifican facility populated with plenty of bad guys, plenty of exploding barrels, plenty of destructible stalactites, and an always-fun cart ride through it all. I’ve also been given a glimpse of an unfathomably enormous enemy -- a four-legged, 800-foot tall land-stomping robot -- that will be emerging later during the climax of Fracture’s first act. The size of the thing, and the sheer airspace it will take up, is something Day 1 has kept under wraps so far, but gave us a quick glimpse of during their opening presentation in the LucasArts Theater.

Barring that, I was equally impressed with a puzzle-solving room I’d encountered at the tail end of our one-hour play session. Jet Brody is in a room that serves as a conduit for the construction of Hydra Balls (explosive, spherical constructs that are essentially rolling landmines). One drops into the center of the room, and I need to utilize the Entrencher to carve a pathway that will make the Hydra Ball route properly and explode against the surrounding machinery. It’s the perfect opportunity to turn the otherwise chaotic Entrencher into a more surgical tool for Terrain Deformation.

Let me be clear: The videos and screenshots for Fracture have been underwhelming at best. My previous criticisms of the bland environments, Jell-O ground warping, and low-gravity vehicle airiness all stemmed from a place of genuine concern (and perhaps some bad Taco Bell that day). But once I got my hands on the game, it became quite impossible not to enjoy the time given. The Day 1 programmers deserve an award themselves simply for overcoming the unheard-of technical hurdles that the design team devised. (“When we put the list of what we wanted to do, next to the list of what we could afford to do … the lists were nearly identical,” said Day 1.)

And while I lazily wrote off Fracture as nothing more than a “gimmick” from the beginning, seeing how fully-integrated Terrain Deformation works throughout the game will undoubtedly force anyone to reexamine their preconceived stance. I don’t want to overstate that, however: This isn’t necessarily a “coming to Jesus” moment with everyone in the audience swooning with an inexplicable change of heart, but I’ll admit that when broken down into its chemical components, it’s hard not to grow increasingly impressed with Fracture’s ability to seal its own deal. Plus the story arc, though served with a generous helping of vanilla when it comes to characterization -- at least so far -- at least pushes beyond the “aliens are attacking; so kill ‘em” industry standard for action-shooter storytelling. In short, Fracture is a game that probably won’t change your mind about it until you get some actual face time with its mechanics.

We’re treading hallowed ground and we know it. With an awe typically reserved for Gothic cathedrals and Wonders of the World, we tip our chins up and gape around at the stylistically-preserved historical architecture. We also wonder if at any moment George Lucas himself might emerge from around a bend in the pathway, or stroll out of any one of the buildings, coffee in one hand, lightsaber in the other.

We don’t see George Lucas or lightsaber at his hip, but this is indeed the home of Lucasfilm, LucasArts and ILM (Industrial Light & Magic). These arms of George’s empire are encased in a building known as the Letterman Digital Arts Center -- built from the ground up to preserve the architectural style of the original hospital that was on this particular site, but containing all the amenities of a contemporary office space. And if it wasn’t for the Yoda fountain in the courtyard, you might not fully realize at first that you’re standing at the center of the Star Wars universe.

Chris Cook, Public Relations Specialist for LucasArts, is walking and talking our way through the hallways toward our destination: The LucasArts Gameplay Room. Two trashcans (already stuffed with lidded coffee cups and snack wrappers) sit outside the Gameplay Room’s door, reminding us that food and drink are a no-no inside. And as we step through the door we’re greeted by two rows of tables, each table lined with ten gaming stations heavily-equipped with a PC, Xbox 360, PS3, PSP, and HD monitor. Each monitor has a handwritten nametag propped at the top with designations like “Xbox 360 Italy” and “PS3 Japan,” presumably to help us remember which station we were at in the event of a restroom break. Cool air blankets the room through copious vents positioned on the ceiling and floor. The chairs are ergonomic perfection. And the main menu for Fracture, developer Day 1 Studios’ latest high-budget baby, is humming on the screens (“These aren’t the best monitors,” says a Day 1 dev as I manually brighten the dark screen through Fracture’s options menu).

To get you up to speed: Fracture takes place in the year 2161. Day 1, developers of the award-winning MechAssault series, wanted to look at hot-button topics of today like stem cell research, the Human Genome Project, and global warming, then fast-forwarding their potential effects 153 years -- focusing on a few worst case scenarios, but trying not to grow preachy in the telling (“We don’t want to slap players around with a case in Ecological Policy”). Nonetheless, global warming has raised water levels, turning the Midwest into a great inland sea. The East Coast, now dubbed the Atlantic Alliance, protected itself from a similar fate by utilizing Terrain Deformation technology: the ability to raise and lower the landscape at will. The West Coast, now the Republic of Pacifica, followed suit. Not only geographically, but ideologically the United States became a house divided. The Atlantic Alliance advanced itself technologically by utilizing cybernetic enhancements. The Pacificans resorted to DNA splicing and genetic manipulation. Washington D.C. grew increasingly displeased with the West and, far too late in the ballgame, decided to criminalize the Pacificans’ research and actions.

An Atlantic Alliance team, spearheaded by Colonel Roy Lawrence and his adopted son Jet Brody, is sent to a dried-up San Francisco Bay (“We wanted to incorporate water physics with Terrain Deformation, but that’s one place where the programmers successfully punched us in the face and we fell on the ground,” said Day 1) in order to bring the leader of the Pacifican resistance, Colonel Nathan Sheridan, back to D.C. to be tried for war crimes and, assuredly, treason.

Consider yourself briefed.First up on the LucasArts Gameplay Room agenda is an hour’s worth of Fracture’s single-player campaign. It begins with the in-game tutorial, which is 100 percent identical to the demo released on Xbox LIVE and PlayStation Network September 18th. The showdown between Jet Brody and Colonel Sheridan comes to a head at Alcatraz Island. Sheridan, naturally, isn’t ready to walk away in cuffs, and the chase is on. Previously unknown through Jet Brody’s intel, however, is the fact that Sheridan has been preparing an all-out war effort for longer than initially conceived. Things will indeed get worse before they get better.

I push full-bore through the Alcatraz Island demo material until Jet Brody hops on a dropship and is airlifted towards his next target: the Golden Gate Bridge. Anti-aircraft gunfire cuts that objective short during a cutscene. Jet Brody’s ride is picked out of the air and goes down hard. He’s the sole survivor amidst the wreckage, but his comms are clean and his commanding officer, Colonel Lawrence, instructs him to press on -- army of one-style -- and proceed to the bridge as ordered. Jet Brody may have jokes, but he’s not insubordinate. Not yet, anyway. Both the Pacific and Atlantic forces seem suspect.

As I quickly acclimate to the tools of the trade -- to include the wrist-mounted Entrencher (“The key that unlocks the world of Fracture,” states Dan Hay, Executive Producer and Art Director for Day 1), Tectonic Grenades (which raise the terrain), and Subsonic Grenades (which do the opposite) -- I steer Jet through a complex of mammoth bunkers housing the two anti-aircraft guns that blew up Jet Brody’s ride.

Along the way I face plenty of Pacifican fodder, tossing them into the air when I burst the ground up from under them and skeet shooting their ragdoll bodies on the way down. Other times I raise terrain to provide immediate cover in the often times wide-open battlefields, or dig a trench to grant myself breathing room from the flying bullets overhead. The enemy is more than capable of utilizing its own tools for terrain deformation, flanking the mounds of earth from the left and right, climbing right over the top to gain a height advantage over my position, or falling back in order to recover shields. Creating a seemingly strong enemy AI in a corridor shooter like F.E.A.R. is all well and good, but that game’s AI didn’t have even a fraction of the variables being tossed about in Fracture. Here, as the battlefield tosses up and down like a stereo equalizer, the AI has to be able to cope with keeping track of a player that moves not only on the X-axis, but on a constantly variable Y-axis as well -- and we’re of course not just talking about Y-axis movement on a couple stationary staircases. While the AI may lose track of you on the Casual difficulty level (you will hear the bad guys shouting out, “Where’d he go?”) the hardcore difficulty setting creates a drastically different scenario, with a relentless enemy that -- even if it doesn’t know your exact location on the other side of that mound -- is willing to toss a grenade up and over at your last estimated location. Like 3-D Battleship.

The Day 1 team tells me that Fracture was initially conceived to be a first-person shooter, but realized how disorienting it was to raise up large mounds of dirt in front of your face that took up your entire field of view. Day 1 quickly concluded the need to pull back to a third-person perspective, just to keep a player’s bearings in the radically chaotic fields of battle. The only drawbacks to that decision was the lack of a near-object fade that can sometimes have foliage (a rare occurrence) that’s hanging five feet behind you suddenly choke a player’s line of sight. Another issue is that Jet Brody’s firing stance often has him holding a rifle down by his waistline: He’s literally shooting from the hip. And reconciling the difference between that low-slung firing position and the eye-level reticule can be a chore for the player. Jet Brody can also kneel behind objects, but it’s only under infrequent circumstances that he can fire at enemies from that kneeling position. A player has to pop up, fire off some rounds, and then recover.Day 1 also, in the best interests of the wildly changing landscape, had to do away with allowing a prone position, which is always ideal for sniping, but awkward in implementation when you could be humped over a hill one moment and bent over backwards the next at the bottom of a trench. They also didn’t allow Jet Brody to ‘hug’ up against cover. Very little is stationary on a Fracture battlefield, with crates, barrels, and boulders getting tossed around with trampoline-like enthusiasm, not to discount the screen-shaking explosions, dust, and debris scattering every which way. And while there’s little “verticality” to worry about (an up and coming buzzword in action-shooter gameplay), having to draw a bead on an enemy that’s rarely on a level plane with you can be challenge enough.

Not only is Terrain Deformation required to manage the battlefield, it also serves as a puzzle-solving tool once the bullets stop flying. Jet Brody doesn’t make a habit of looking around enemy structures for door keys, though he can push gates open with the Entrencher. He may not have a person on the inside opening gates for him to progress through, but he might lower the terrain to uncover a hidden tunnel or weak point in the infrastructure. Or a set of stairs may be blasted completely away, but reaching the second story of a building is doable with Spike Grenades (which lifts a pillar of earth into the sky that can be ridden to upper levels). It is a world built around and for Terrain Deformation. Little of what I previewed is designed without this tool in mind, and without it there’s very little progression through the world.

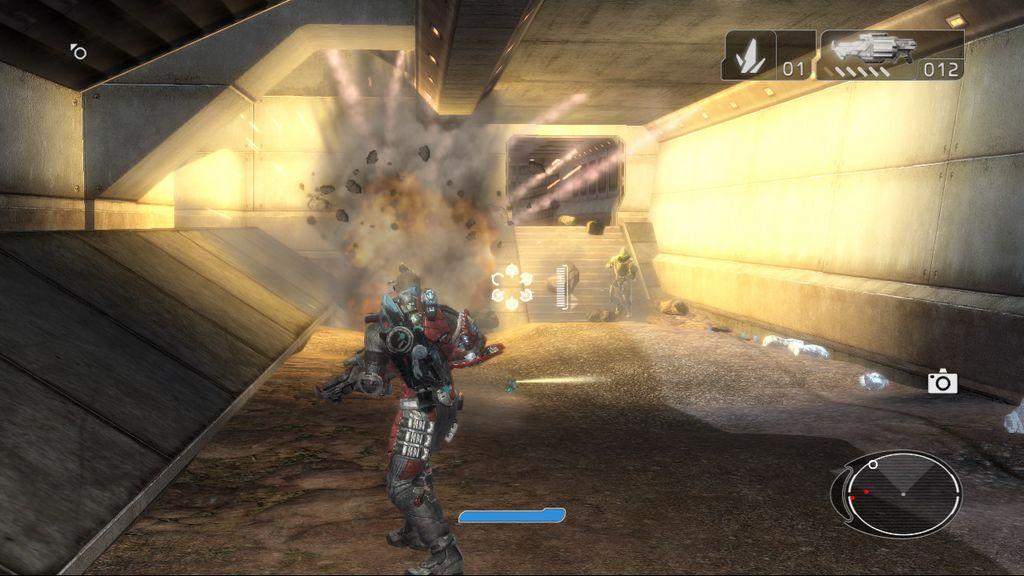

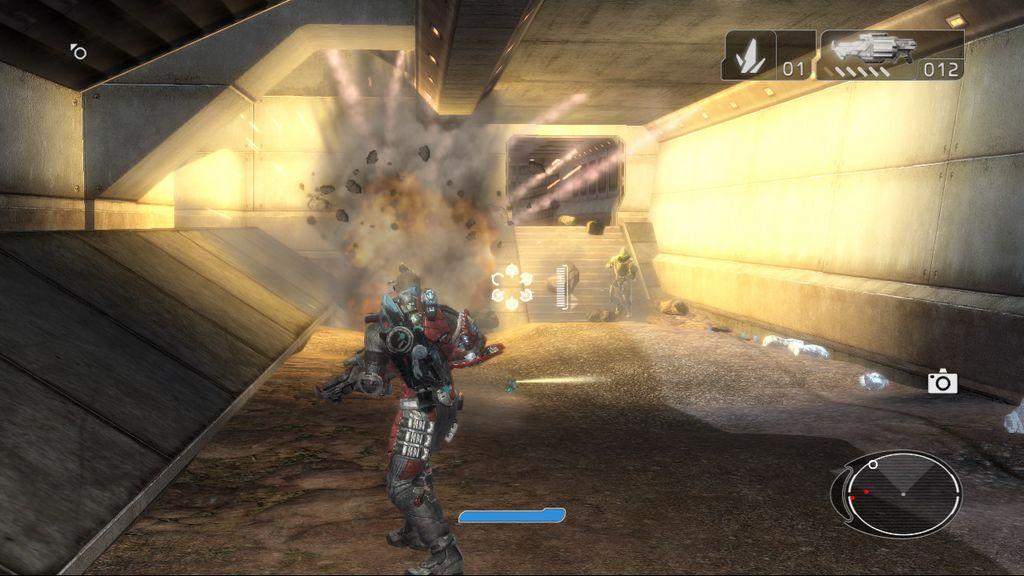

I’ve been proceeding with a stop-and-go frequency through an underground Pacifican facility populated with plenty of bad guys, plenty of exploding barrels, plenty of destructible stalactites, and an always-fun cart ride through it all. I’ve also been given a glimpse of an unfathomably enormous enemy -- a four-legged, 800-foot tall land-stomping robot -- that will be emerging later during the climax of Fracture’s first act. The size of the thing, and the sheer airspace it will take up, is something Day 1 has kept under wraps so far, but gave us a quick glimpse of during their opening presentation in the LucasArts Theater.

Barring that, I was equally impressed with a puzzle-solving room I’d encountered at the tail end of our one-hour play session. Jet Brody is in a room that serves as a conduit for the construction of Hydra Balls (explosive, spherical constructs that are essentially rolling landmines). One drops into the center of the room, and I need to utilize the Entrencher to carve a pathway that will make the Hydra Ball route properly and explode against the surrounding machinery. It’s the perfect opportunity to turn the otherwise chaotic Entrencher into a more surgical tool for Terrain Deformation.

Let me be clear: The videos and screenshots for Fracture have been underwhelming at best. My previous criticisms of the bland environments, Jell-O ground warping, and low-gravity vehicle airiness all stemmed from a place of genuine concern (and perhaps some bad Taco Bell that day). But once I got my hands on the game, it became quite impossible not to enjoy the time given. The Day 1 programmers deserve an award themselves simply for overcoming the unheard-of technical hurdles that the design team devised. (“When we put the list of what we wanted to do, next to the list of what we could afford to do … the lists were nearly identical,” said Day 1.)

And while I lazily wrote off Fracture as nothing more than a “gimmick” from the beginning, seeing how fully-integrated Terrain Deformation works throughout the game will undoubtedly force anyone to reexamine their preconceived stance. I don’t want to overstate that, however: This isn’t necessarily a “coming to Jesus” moment with everyone in the audience swooning with an inexplicable change of heart, but I’ll admit that when broken down into its chemical components, it’s hard not to grow increasingly impressed with Fracture’s ability to seal its own deal. Plus the story arc, though served with a generous helping of vanilla when it comes to characterization -- at least so far -- at least pushes beyond the “aliens are attacking; so kill ‘em” industry standard for action-shooter storytelling. In short, Fracture is a game that probably won’t change your mind about it until you get some actual face time with its mechanics.

* The product in this article was sent to us by the developer/company.

About Author

Randy gravitates toward anything open world, open ended, and open to interpretation. He prefers strategy over shooting, introspection over action, and stealth and survival over looting and grinding. He's been a gamer since 1982 and writing critically about video games for over 20 years. A few of his favorites are Skyrim, Elite Dangerous, and Red Dead Redemption. He's more recently become our Dungeons & Dragons correspondent. He lives with his wife and daughter in Oregon.

View Profile